The ocean has absorbed most anthropogenic heat and carbon dioxide emissions since the start of industrialization. But its capacity to do so is not unlimited, and its role in climate-change mitigation and adaptation should not be reduced to this single, abstract function.

VICTORIA – Next week, governments and civil-society organizations from around the world will gather in Nice, France, for the United Nations Ocean Conference. The third such meeting since 2017, the UNOC comes at a time when countries are also finalizing their updated Nationally Determined Contributions (decarbonization plans) as required under the Paris climate agreement.

Trump’s Unworkable Trade Formula

Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images

2

The Tragedy of Emmanuel Macron

Yves Herman/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

4

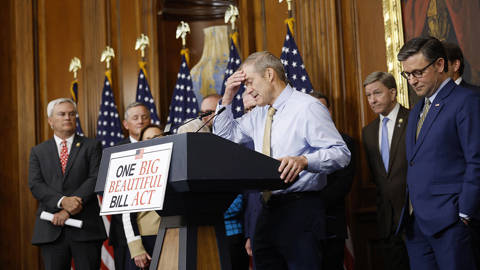

US Fiscal Irresponsibility Is Everyone’s Problem

Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

1

The timing is fitting, because changes in our oceans have become a familiar barometer for the severity of the climate crisis. Vibrant, technicolor coral reefs, once bursting with life, are being bleached ghostly pale by warming, acidic waters. Island populations, such as the inhabitants of the largest of Panama’s Cartí Islands, are being forced to abandon their homes in the face of rising sea levels. And many coastal communities, often some of the poorest in the world, are being ravaged by increasingly severe cyclones.

As the ones on the front line, small island developing states are also leading sources of climate innovation. We have become test beds for solutions that can guide action globally. From our perspective, the ocean is not just a symptom of a changing climate, but also a major part of the solution.

The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (of which the Seychelles is a member) estimates that some 35% of the emissions reductions needed by 2050 could come from the ocean. Most of this potential lies in industrial sectors – from decarbonized shipping to marine-based renewable energy. But the protection and restoration of certain “blue carbon ecosystems” – mangroves, seagrasses, saltmarshes – can also measurably contribute to climate-change mitigation efforts.

In our own 2021 NDC, the Seychelles committed to mapping and subsequently protecting all seagrasses across our exclusive economic zone – an area totaling 1.3 million square kilometers (503,000 square miles) – by 2030. Now, I am proud to say that we have already met that goal, protecting over 99% of our seagrass meadows five years ahead of schedule. In doing so, we have set a benchmark for ocean-climate leadership. Other countries across the Western Indian Ocean are now undertaking similar work and outlining their own ambitions for the 2025 NDC updates.

In addition to serving as a measurable source of carbon storage, these ecosystems are some of the most effective and cost-efficient forms of natural infrastructure available for stabilizing shorelines and buffering storms. They provide a vital first line of defense for islanders and coastal dwellers, absorbing wave energy, filtering water, and preventing erosion. And they also underpin the blue economy on which billions of livelihoods depend.

PS Events: London Climate Action Week 2025

Don’t miss our next event, taking place at London Climate Action Week. Register now and watch live on June 23 as our distinguished panelists discuss how business can fill the global climate-leadership gap.

Register Now

In fact, seagrasses alone “provide valuable habitat to over one-fifth of the world’s 25 largest fisheries,” including many species that are key to local food security and incomes. Healthy coastal ecosystems mean healthier economies, more resilient communities, and greater long-term stability. With healthy mangroves and seagrasses, frontline communities are far more resilient and better able to adapt to climate change.

Our experience offers important lessons. While the ocean has long been described as the planet’s greatest “carbon sink,” that is a dated construct. The ocean has indeed absorbed most anthropogenic heat and carbon dioxide emissions since the start of industrialization. But its capacity to do so is not unlimited. There is no magic “plug hole” where heat and carbon simply disappear. Depicting the ocean this way risks obscuring the tangible, place-based role of marine ecosystems in supporting many communities’ cultures, diets, identities, and survival. For Seychellois, seagrass meadows are far more important as a habitat for the rabbitfish that sustain artisanal fishers, or as a source of food and shelter for the turtles that attract so many tourists, than they are as carbon sinks.

Reducing the value of three-quarters of our planet to the singular role of carbon sink overlooks the ocean’s vast contributions to food security, cultural identity, and economic resilience. This narrow framing reinforces the inequities baked into how we assess, govern, and invest in planetary systems.

Ultimately, industrial marine sectors and natural ecosystems are underused tools in addressing climate change and other development needs. As world leaders gather in Nice and prepare for the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Belém (COP30), they can take inspiration from the Seychelles in championing ocean-based climate action.

We must not treat the ocean as an afterthought or a technical fix, but rather as a central pillar of the climate agenda. The ocean’s role as a “carbon sink” has bought us precious time, but at a huge cost in terms of its vibrancy and abundance. For the long-term health of people and the planet, preserving ocean health is essential.

VICTORIA – Next week, governments and civil-society organizations from around the world will gather in Nice, France, for the United Nations Ocean Conference. The third such meeting since 2017, the UNOC comes at a time when countries are also finalizing their updated Nationally Determined Contributions (decarbonization plans) as required under the Paris climate agreement.

Trump’s Unworkable Trade Formula2

The Tragedy of Emmanuel Macron4

US Fiscal Irresponsibility Is Everyone’s Problem1

The timing is fitting, because changes in our oceans have become a familiar barometer for the severity of the climate crisis. Vibrant, technicolor coral reefs, once bursting with life, are being bleached ghostly pale by warming, acidic waters. Island populations, such as the inhabitants of the largest of Panama’s Cartí Islands, are being forced to abandon their homes in the face of rising sea levels. And many coastal communities, often some of the poorest in the world, are being ravaged by increasingly severe cyclones.

As the ones on the front line, small island developing states are also leading sources of climate innovation. We have become test beds for solutions that can guide action globally. From our perspective, the ocean is not just a symptom of a changing climate, but also a major part of the solution.

The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (of which the Seychelles is a member) estimates that some 35% of the emissions reductions needed by 2050 could come from the ocean. Most of this potential lies in industrial sectors – from decarbonized shipping to marine-based renewable energy. But the protection and restoration of certain “blue carbon ecosystems” – mangroves, seagrasses, saltmarshes – can also measurably contribute to climate-change mitigation efforts.

In our own 2021 NDC, the Seychelles committed to mapping and subsequently protecting all seagrasses across our exclusive economic zone – an area totaling 1.3 million square kilometers (503,000 square miles) – by 2030. Now, I am proud to say that we have already met that goal, protecting over 99% of our seagrass meadows five years ahead of schedule. In doing so, we have set a benchmark for ocean-climate leadership. Other countries across the Western Indian Ocean are now undertaking similar work and outlining their own ambitions for the 2025 NDC updates.

In addition to serving as a measurable source of carbon storage, these ecosystems are some of the most effective and cost-efficient forms of natural infrastructure available for stabilizing shorelines and buffering storms. They provide a vital first line of defense for islanders and coastal dwellers, absorbing wave energy, filtering water, and preventing erosion. And they also underpin the blue economy on which billions of livelihoods depend.

Don’t miss our next event, taking place at London Climate Action Week. Register now and watch live on June 23 as our distinguished panelists discuss how business can fill the global climate-leadership gap.

Register Now

In fact, seagrasses alone “provide valuable habitat to over one-fifth of the world’s 25 largest fisheries,” including many species that are key to local food security and incomes. Healthy coastal ecosystems mean healthier economies, more resilient communities, and greater long-term stability. With healthy mangroves and seagrasses, frontline communities are far more resilient and better able to adapt to climate change.

Our experience offers important lessons. While the ocean has long been described as the planet’s greatest “carbon sink,” that is a dated construct. The ocean has indeed absorbed most anthropogenic heat and carbon dioxide emissions since the start of industrialization. But its capacity to do so is not unlimited. There is no magic “plug hole” where heat and carbon simply disappear. Depicting the ocean this way risks obscuring the tangible, place-based role of marine ecosystems in supporting many communities’ cultures, diets, identities, and survival. For Seychellois, seagrass meadows are far more important as a habitat for the rabbitfish that sustain artisanal fishers, or as a source of food and shelter for the turtles that attract so many tourists, than they are as carbon sinks.

Reducing the value of three-quarters of our planet to the singular role of carbon sink overlooks the ocean’s vast contributions to food security, cultural identity, and economic resilience. This narrow framing reinforces the inequities baked into how we assess, govern, and invest in planetary systems.

Ultimately, industrial marine sectors and natural ecosystems are underused tools in addressing climate change and other development needs. As world leaders gather in Nice and prepare for the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Belém (COP30), they can take inspiration from the Seychelles in championing ocean-based climate action.

We must not treat the ocean as an afterthought or a technical fix, but rather as a central pillar of the climate agenda. The ocean’s role as a “carbon sink” has bought us precious time, but at a huge cost in terms of its vibrancy and abundance. For the long-term health of people and the planet, preserving ocean health is essential.